IEX 174: Exponential Strategies

Once we understand exponentials, how do we shape our strategy making?

Exponential Times

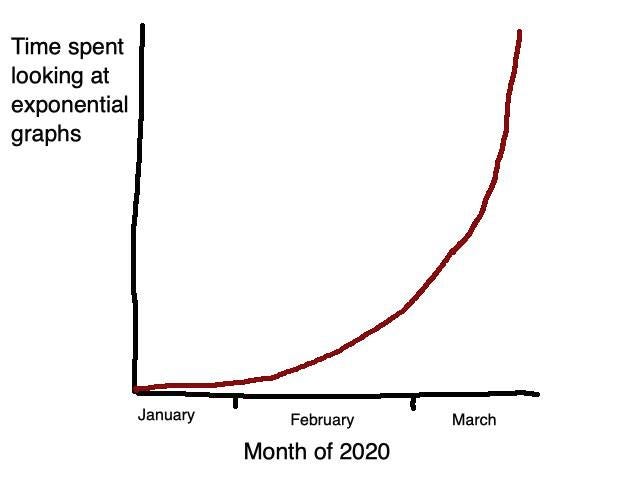

We know now that these are exponential times. If any doubts lingered, then Covid19 gave us a harsh lesson in understanding how exponentials work. The graph below is a tongue in cheek take on our collective appreciation of exponentials.

Here are two more simple examples to get your head around, both based on popular riddles. The first, which you should try to answer within 3 seconds, goes thus: if the lilies in a pond double every day, and will cover the entire pond in 30 days, then when will the pond be half full of lilies? You have to control your instinct to say 15 days because the answer is 29 days. Or to put it another way, if the lilies in a pond represent an epidemic, then on day 23 of 30 you might still be unconcerned because less than 1% of the pond is covered. Even on day 27 it's barely crossed 10%.

Coverage of the pond by lilies

Day 30 = 1 = 100%

Day 29 = 1/2 = 50%

Day 28 = 1/4 = 25%

Day 27 = 1/8 = 12.5%

Day 26 = 1/16 = 6.25%

Day 25 = 1/32 = 3.125%

Going all the way back, on day one, the coverage is 1/ 536870912, an infinitesimally small number.

Typically, the scientists are screaming on day 5 when the coverage is 0.00000003. The decision makers will only wake up around day 20, and take a decision hopefully by day 25. By then our ability to control the epidemic is long gone.

Here's another example - you may know the popular riddle about the king who offered a reward to a loyal subject - he offered him gold, land, titles, but the man only asked for grains of rice on a chess board. He requested just one grain of rice on the first square, and double the amount on every successive square. According to the story, the king consented easily but was ruing his decision less than half way through the board. If you've heard this you probably know its a very big number by the time we get to the 64th square of the board, but it may still surprise you that the number on the 64th square would be about 10 times the global production of rice today.

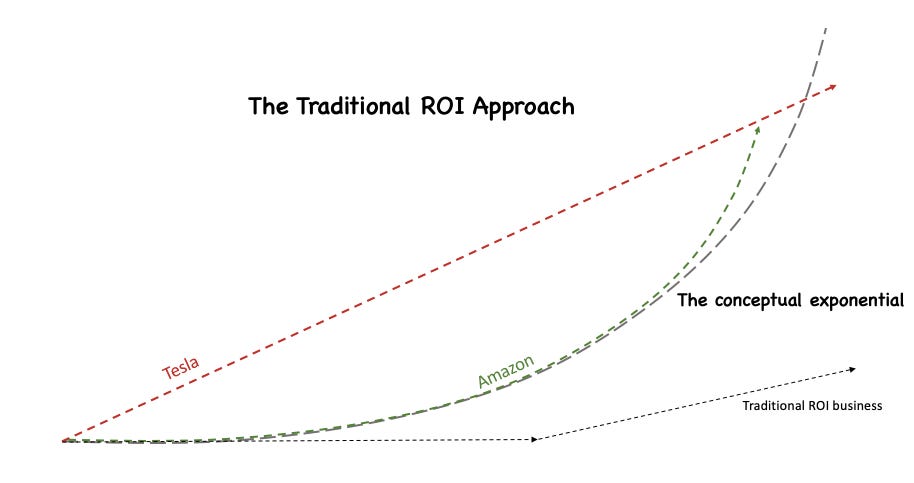

Small wonder then that we find it hard to deal with exponentials. And for most businesses this is a huge challenge, because ROI calculations are rarely based on exponential thinking. Largely justifiably so, because the future scenarios come with a lot of uncertainty (so you have to use probabilistic estimates across multiple scenarios), and because the exponential factor is also not always clear and may change, or be impacted by a number of events, so its a moving target. Which makes the response of some of the exponentially successful companies all the more laudable.

If you still want to get your head around exponentials, I would recommend 3 books: the first is Exponential Organisations, by Salim Ismail. The second is Exponential, by Azeem Azhar. And the third is The Inevitable, by Kevin Kelly. The third doesn’t deal specifically with exponentials, but provides useful insights on the kind of discontinuity that exponential technologies create.

Exponential Strategy Types

While we have all started reading about and understanding exponentials, it still remains an important question as to how we actually deal with and react to an exponential world. Let’s look at the idea of a world where technology is driving a conceptual exponential - without locking into any single tech, consider that a lot of aspects of our lives are being driven by the technology exponential curve - from autonomous and electric vehicles, to gene-sequencing and editing, to predictive business models. In sum this means that the world in 10 years will look very different to what we see today, in ways that will tax our imagination.

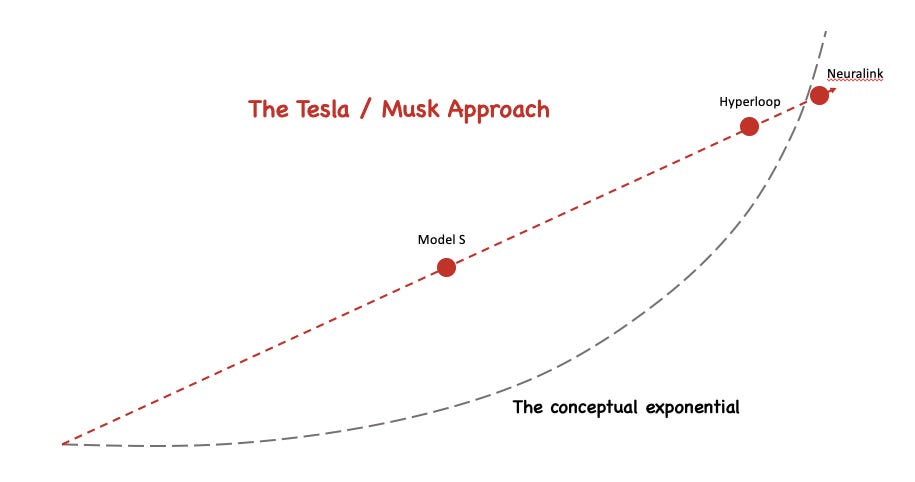

Moonshot: For the most extreme example of dealing with the exponential future, it's hard to look past Elon Musk, Time Magazine's 2021 man of the year. Musk seems to lock into a future scenario and gun straight for that world. He bets that he will have a product that will be perfectly suited for a world that most others can barely imagine, let alone plan for. The Tesla model S rolled out in 2012, the Roadster, 4 years before that. At the time, the idea that a commercially viable car produced at scale could run on a battery was a pipe dream. The global thinking and alignment around sustainability was nascent. The Paris Accord was still in the future. Battery Tech wasn't a thing. None of this stopped Musk from embarking on his big vision and committing himself wholeheartedly to a crazy moonshot idea. Musk is the true exponential planner - he continues to work on ideas far ahead of today.

Neuralink (Brain interfaces), SpaceX, Hyperloop, these are all examples of classic Musk projects. A very good example of his thinking comes from Salim Ismail, the author of 'Exponential Business' who says that when he pointed out that accelerating and decelerating human beings at the rate Hyperloop was planning to do, would kill them, Musk responded with 'yes, its a problem'. Note: not THE problem, just A problem, one of many. But not one that is preventing Musk from pushing ahead because he's betting that he or somebody else will come up with an answer to the problem and he wants to be ready with the market ready solution. Musk's approach is best described as a direct line that ignores the current reality and heads straight for the future state. This is not to suggest that he doesn't course correct. Just that conceptually he ignores the present, or even the immediate future.

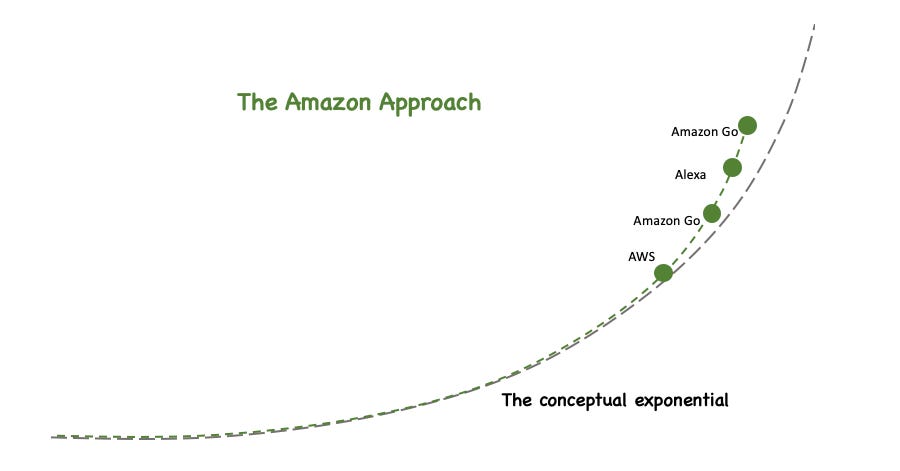

Ride The Curve: A different but equally successful strategy of course is that of Jeff Bezos, who 'rides the exponential. In his recent book, Invent and Wander, which includes his shareholder letters for 20 years of Amazon's operations, he says somewhere around 1997, that his core model of eCommerce can not only be extended beyond books to any category, but that its core economic model is dependent on processing, data storage, and bandwidth, all of which are doubling in price performance every 18, 12, and 9 months respectively. And so there's no way any physical retail model can compete with that.

Amazon's growth therefore is built not on moonshots, but sitting on the exponential and riding it. Amazon is the master of adjacent innovation - even AWS, or the Kindle, or Amazon Go come from the rib of the existing businesses and there's a clear and visible lineage. Amazon doesn't stray too far from the exponential line and its own trajectory. This might sound tame in comparison with Tesla and Musk but let’s not forget that for over a decade, Bezos flew in the face of conventional market wisdom and negative coverage from analysts.

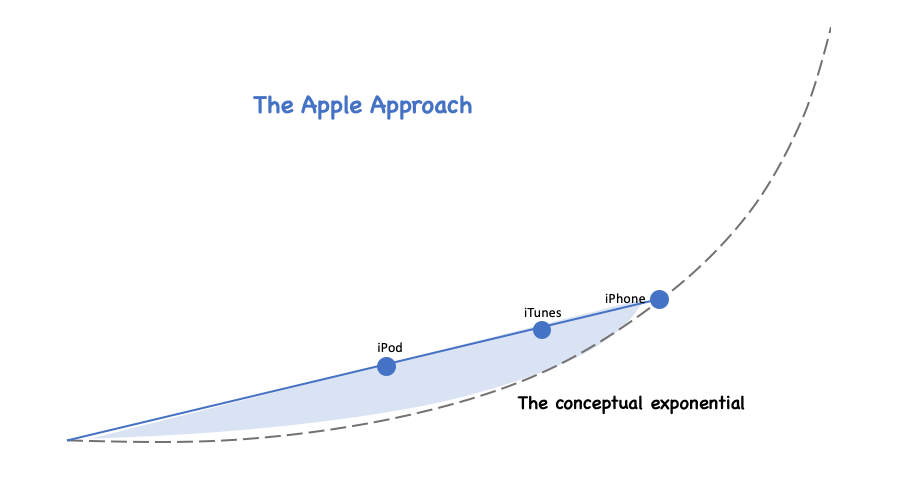

Lift the Curve: And what about Apple? Under Steve Jobs, Apple's strategy seemed to be more disruptive and forward thinking. But even under Jobs, Apple wasn't looking at some distant, non-specific scenario. And even more importantly, Apple actually drove the exponential curve through the iPhone. The world before the iPhone was a very different one.

Post Steve Jobs, Apple has been more of a software and platforms innovator, and less of a device led disruptor, but it's more akin to Amazon in that its riding the exponentials especially around Healthcare, Automobiles, and even enterprise technologies.

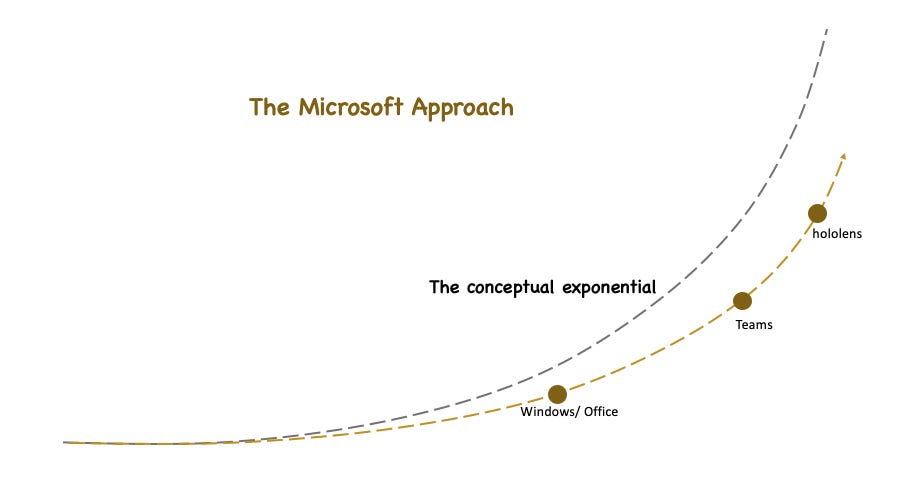

Follow The Curve: A successful following strategy is typified by Microsoft. Rarely investing far ahead of the curve, Microsoft is very good at picking up the market signals, and directions, and being a fast follower. Whether you look at Windows, or Teams, or Azure, or even Hololens. These are all driven via acquisitions, or fast following. What is creditable is the ability to commit to a change of strategy once the direction is clear. Way back in the mid 1990s, having ignored the emerging Internet business models, Bill Gates wrote a famous memo, calling out an about turn for the company, scrapping billions of dollars of investment, and repositioning the company around the Internet.

Its worth pointing out that these differences are not reflections of how people think but how they act. Bezos or Musk may or may not have wildly different views of the future. We don’t know. But their willingness to commit investment and effort ahead of the curve is different.

Grab The Inflexion Point: A lot of companies find themselves on the exponential curve because of what they do - their product and business model. Usually a lot then depends on how much is at stake. Kodak or Blockbuster, or even Blackberry and Nokia were unable to jettison their existing business model because they had too much invested - and their structures, power bases, and executives were all locked into the old model. Conversely, Netflix had barely started scaling its DVD rental business when the realisation set in that the future was not about physical media at all. There are some excellent examples of large companies that have hit an epiphany about the future of their business and have been able to successfully morph the business. Philips (Healthtech), Bosch (Automotive & Mobility software), and Siemens (Industrial IOT) are 3 companies in Europe which come to mind.

Miss The Curve: Many companies, though, miss the curve, and react late (think day 25 on the lily pond), and because change can be hard, end up further behind because change is treated as one big transformation project. It's not one project, it's a series of continuous adjustments. It's one a project, it's a mindset change. And if you're reacting when your business model is actually threatened, you may be playing catch up for a while.

Looking at the last 30 years, the conceptual exponential - the collective technology landscape - has been driven by a vast number of developments. Key among them are the internet, the smart phone, cloud computing and battery tech / autonomous vehicles. The last of these is still playing out. But while companies such as Amazon, Tesla, and Apple have all impacted the exponential through their own strategies, their approach, in retrospect has been very different, and while this is just my analysis of how they differ, it's dangerous to club all innovators and approaches into a one-size-fits-all model of disruption or innovation.

Reading This Week

(This week’s reading is inspired by disruption and exponentials)

Nuclear Fusion - is gaining popularity with investors. Fusion has the potential to be one of the greenest sources of energy. But how far are we from commercialisation? (TechCrunch)

Solid-state lithium-ion batteries can offer a 10x improvement in performance. Here’s the story of their path to commercialization. (Popular Mechanics)

Future Think: Ben Evans (A16Z) produces an annual presentation highlighting the future. Here’s this year’s edition - where he talks through the evolution of metaverse, the future of collaboration and other themes. (Ben Evans)

Drones at Work: The Brent Cross development, in my old neighbourhood is actively using drones for surveying the landscape. (Smart Cities World)

AWS AI Chips: All the hyperscalers are building custom microchips for better AI performance. Amazon has just announced Graviton 3 and Titanium 2. (Digits to Dollars0

Health Economics: The economic cost of poor health for Europe is around $2.7 Trillion in lost GDP. Focusing on prevention, and driving innovatin are among the needs of the day. (McKinsey)

Almost Sci-Fi: Time Crystals are like perpetual motion systems. Google scientists are using quantum computing to create them.