IEX 160: 6 Innovation Patterns, A Darwinian View

The real story of Charles Darwin's work and discoveries contain some interesting lessons about the patterns of innovation.

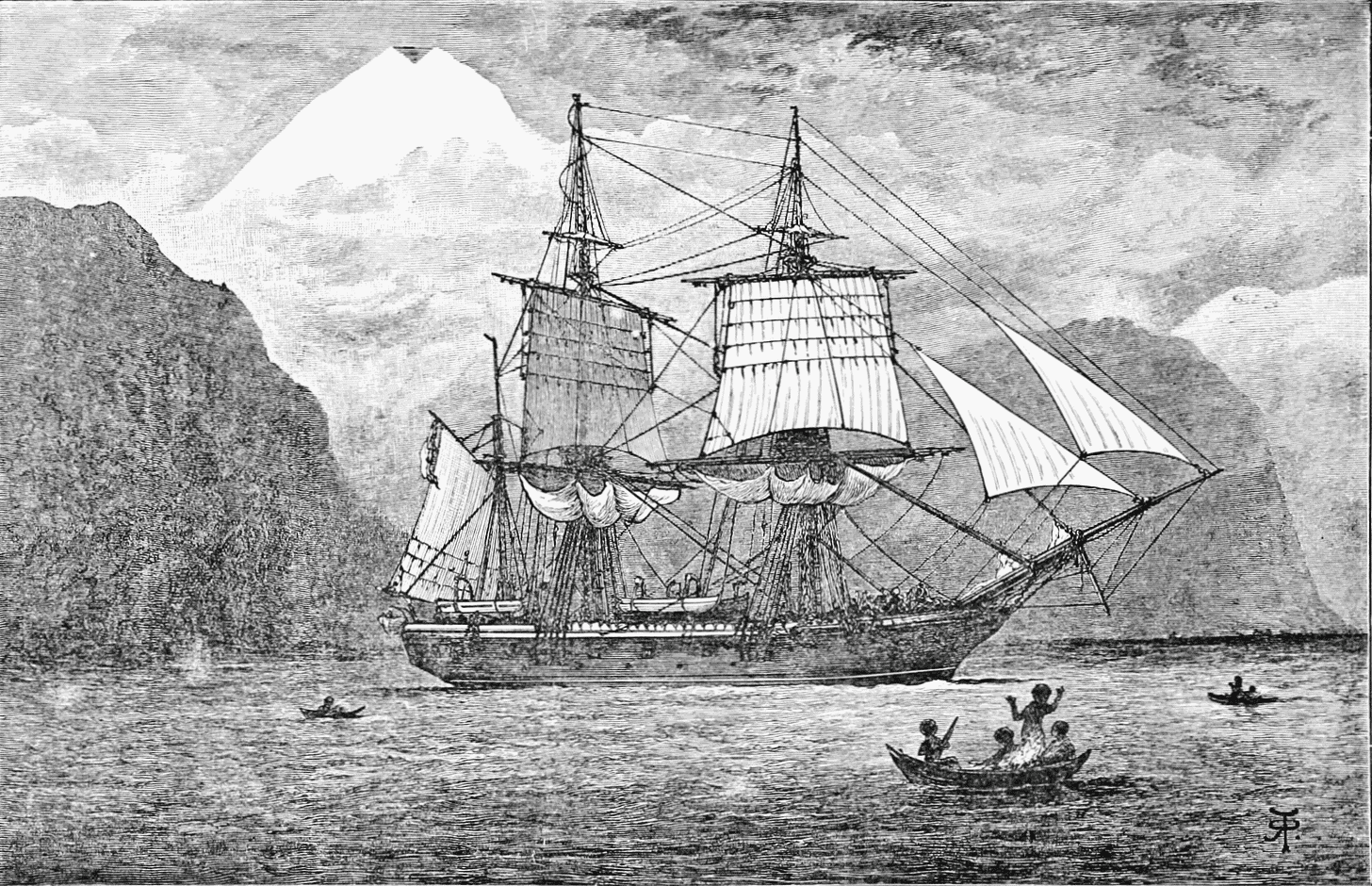

Charles Darwin sailed on the HMS Beagle, and during his voyage he came to study the flora and fauna of the Galapagos islands, which led him to construct one of human kinds most cherished theories, about evolution of species. This is the one line summary most of us are taught and for many of us this is the version we remember. Yet, like a whole lot of invention and discovery stories, the story is far more complex. What's hidden in there, is actually some of the most common patterns of innovation.

First of all, Darwin didn't plan on being a naturalist. Although he always veered towards the area, he was initially studying medicine and later, he was enrolled an arts curriculum, to become a parson. Studies of natural phenomenon was a burning hobby for him, and it was this interest and work that led him to being included almost as an 'extra' on the HMS Beagle voyage. Although there are people who decide very early what they want to do with their lives, (such as Tiger Woods, or Felix Baumgartner), a lot of times what we believe is a deterministic path is actually a fortuitous turn of events. It is nonetheless true, that when the moment comes we need to recognise our calling and are willing to dedicate our life and our time to the cause. Van Gogh didn't start out being a painter, and actually experimented with many careers and indeed many forms of art before discovering his style.

Second, Darwin wasn't a first choice for the HMS Beagle Crew. Apparently they asked a number of people to join and were refused. As highlighted by Yuval Harari in Sapiens, the ship's captain, Robert Fitzroy, was an amateur scientist and offered a number of geologists the chance to join the expedition which were all turned down. He finally offered the role to Darwin who was at the time a 22 year old Cambridge graduate.

Third, the voyages of the Beagle (Darwin went on the second one) owes much to the constant support of the sciences by the 'empire' - a fact that is often ignored, and also highlighted by Harari. Many of the breakthroughs for which we laud the inventors also owe a debt to public or government funding, and institutional support, and most definitely the body of work they stand on. The role of academic funding in higher education, and the institutional funding for research provided by governments via grants and challenges are just some of the examples. Consider the Graphene Institute set up with funding from the UK and EU, which is now enabling the application of graphene in a number of industries ranging from biomedical to electronics, and from lightweight materials, to battery tech.

Darwin didn't have a Eureka moment - he had hypotheses forming in his mind and took many years to translate his work into a coherent theory. In fact, as we just mentioned, Darwin went onboard the Beagle as a geologist, and dedicated a lot of his time and studies to geological studies. His work as a naturalist was almost a sideline. He took copious notes of the biodiversity in the Galapagos islands but didn't decipher them immediately. In fact he spent months after this interpreting his notes and piecing together the puzzle, the last element of which occurred to him while reading Malthus' work on Population - that proved to be the spark that in Darwins mind lit the lamp that clarified the picture. But he had constructed much of the argument in his head already. The HMS Beagle's voyage lasted from 1831-1836. Darwin's Malthusian moment occurred in 1838. (Ref: The Slow Hunch, a chapter from Steven Johnson's book - "Where Good Ideas Come From"). James Dyson saw a sawmill use cyclone technology to clear sawdust, and thought he might be able to design a new vacuum cleaner. It took him 5 years and 5127 prototypes to get to a commercially viable prototype of a bagless model.

Darwin wasn't the only one - many others were on the same trail as Darwin. This is one of the most surprising, yet now well-accepted patterns of innovation. Almost every innovation or invention is ascribed to a single person but in reality, has almost simultaneously been worked on by a number of people roughly at the same time. Newton and Liebniz both came up with the fundamentals of calculus and accused each other of stealing their idea. Logie Baird, Philo Farnsworth and dozens of others were working on Television prototypes, but it's Baird who is credited with getting there first. In much the same way, Alfred Wallace was independently working on a similar hypothesis and came to much the same conclusions as Darwin, and was a collaborator and co-publisher, when they first published their theory. Yet, Darwin went on to fame while Wallace is barely known today. The point though is that you can argue that even without Darwin's work or had the Beagle sunk on the way to Galapagos, Wallace would have arrived at similar conclusions, and our understanding of evolution would not have suffered too much.

One of the key reasons for the last pattern lies in the interconnection of innovation. As certain technologies or capabilities become available, it opens the door for others to happen. My favourite example of this the evolution of crystallography, which led to the discovery of the double-helix. (Watson and Crick got the glory but Rosamund Franklin was just as critical to the discovery). But the patterns are all around us. Think of the number of innovations enabled by the Internet or the Smartphone. When we get autonomous cars, or as AI evolves, each step will open up new vistas of innovation.

How many of these innovation patterns do you see in your world?

Innovators often discover something tangential to what their primary focus is - don't ignore the oblique ideas.

Circumstance plays a big role in where ideas and breakthroughs happen - but you have to be there to be lucky.

The role of institutions is critical but often in the background - understand how to exploit the available infrastructure

Not all great ideas are 'Eureka' moments, some form slowly - allow your ideas to form and shape

But... almost every good idea is likely to have been thought of by multiple people - so don't dawdle needlessly

What innovations and opportunities are becoming possible thanks to the break through ideas of today, and how are you exploiting this?

Reading This Week

Future Innovation: Greg Satell argues that physical, not digital technologies are driving our future. I disagree about productivity being the right metric, but the direction of travel is interesting.

India: It's not just China, but India as well. Large tech companies might have to rethink their India strategies according to this piece.

AI: For a better understanding AI, stop comparing it to human intelligence. It's simply not the right comparison.

Blockchain: Benyamin Ahmed, a 12 year old boy has made £290,000 by selling Whale artwork as NFTs.

The Brain: How does a brain store memories? How do genes influence your brain? Could we connect the brain to machines? Could we create a brain? What causes neuro-degenerative diseases? Here are some of the ways in which scientists are trying to decipher the secrets of the brain.