Audacious Thinking

Recently at work, we had a conference for which we ran an exercise on audacious thinking. A set of team captains were identified and given under 2 weeks to recruit their teams and come up with an audacious goal for the business. A panel of judges evaluated them and prizes were given for the best ‘audacious goal’. I got a ringside view of this as I was running the event, and I got to work with the teams as a coach, and also to listen in to the judges and their thinking process. To put it succinctly, it was an inspiring experience.

But it also made me realise that audacious thinking is like a muscle that we don’t actually exercise often enough. Although there’s a lot of casual conversation about big ideas, there’s actually not enough effort to build the competence to conceptualise and execute bold ideas. After all over 80% of corporate innovation involves marginal improvements and rightfully so, because it’s low risk, short payback cycles, and a 1% growth on a billion pound business is a very significant return.

There comes a time thought when marginal innovation isn’t enough. It’s necessary but not sufficient. Sometimes you want to… no, have to… go for gold. Aim for the stars, and come up with something really big to go after. In fact, the chances are that years later, you’ll be remembered for those big ideas, not the marginal ones. And businesses will rise and fall, lives will be changed, and industries and sectors will be defined by these crazy ideas.

In the rest of this edition, let’s look at what you need to be able to define and deliver a truly bold, disruptive new idea.

Articulate the Why

The most popular stories everybody knows, involve the moon, and the back-stories of some famous actors. John F Kennedy almost defined the category, or at the very least gave it its most popular nickname when he put the ‘moonshot’ into the lexicon. He also famously called out one of the most critical things about moonshots - we sometimes do them precisely because they’re hard. We do them to test ourselves or sometimes to prove that we can. It’s why George Mallory memorably said ‘because its there’ when asked why he wanted to climb Mount Everest.

When Jim Carrey was a struggling actor, he wrote a ten million dollar check out to himself and kept it in his wallet. When Sylvester Stallone was still trying to make his first big feature film, he had to sell his pet dog to make ends meet while he worked on the script of Rocky.

So your reason might be necessity, or 'because it’s there’, but it’s pretty important to articulate both the goal and the reason for doing it. The authors Collins and Porras, also gave us the idea of BHAG (Big Hairy Audacious Goals) as a hallmark of companies that were not just good, but great. In organisations the articulation is even more important so that there’s a clear and shared idea of what the big goal is.

Aim for Absurd

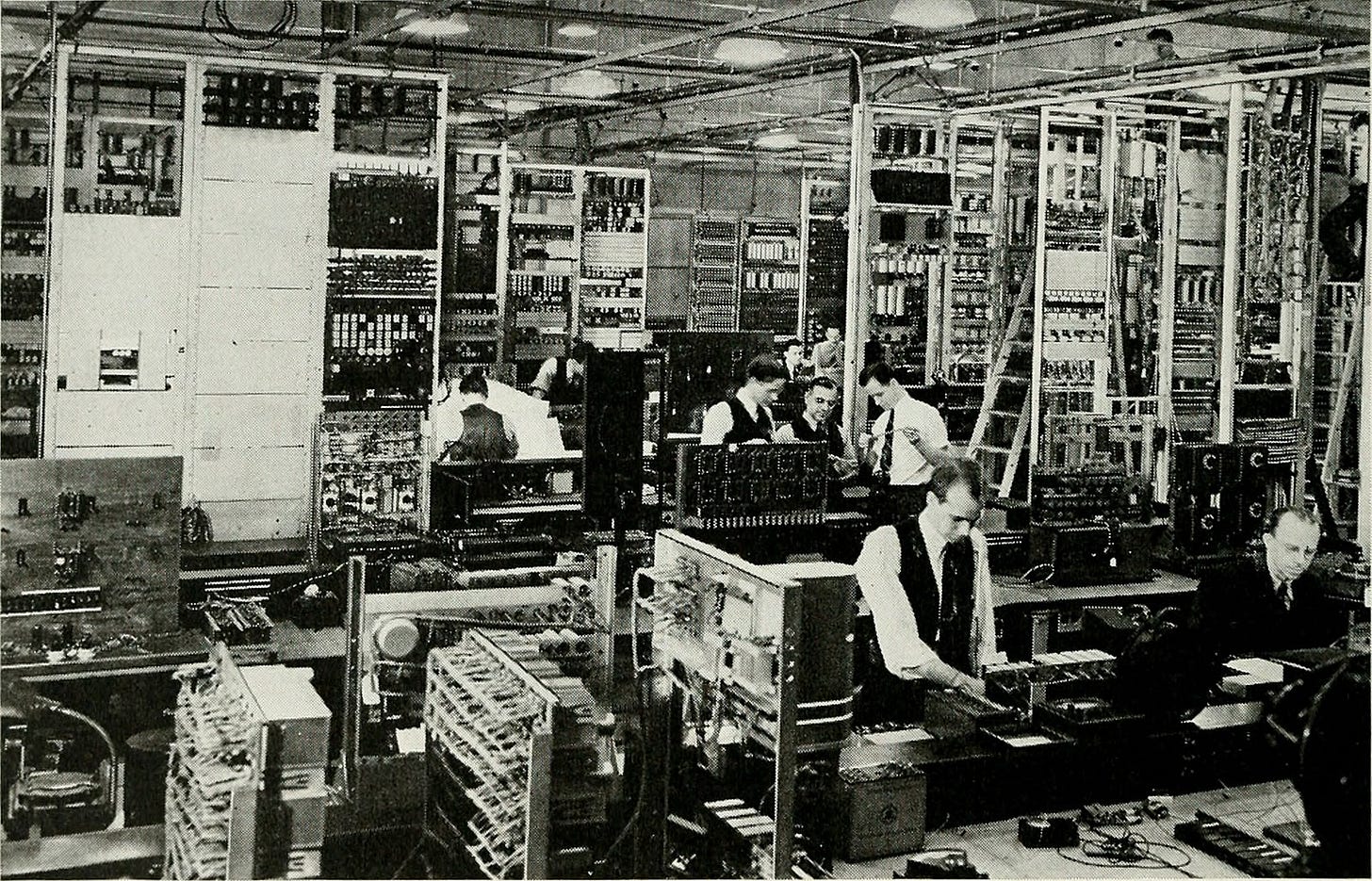

The year was 1909 and AT&T had been tasked with creating a long distance telephony system that would allow calls between New York and San Francisco - across a distance of around 2600 miles. The problem: while the telephone had been invented, everything else was unsolved. At this stage, there was no concept of dial tones, nobody said ‘hello’ on the phone yet. Signals would attenuate over the wire at distance, so you needed to make the wires thicker, but that would increase the weight and cost. You could hold them up with poles, but what if the poles corroded over time through exposure to underground moisture? Would copper or iron work better? Or some other material? How to solve for everything? Faced with this challenge, Frank Jewett, a senior manager (who later became President of Bell Labs), set up what was among the earliest industrial research complexes. He went out and hired the best brains from universities and created an environment with hundreds of research scientists all working on different aspects of the problem. On January 25, 1915 the first long distance call went through from New York to San Francisco.

The Bell Labs research centre continued to contribute inventions and discoveries in a bewildering range of areas over the next decades. The radar, information theory, statistical controls, sound and motion synchronisation for films, photovoltaic cells, and even the earliest silicon based integrated circuit all came from Bell Labs. The Bell Labs have accounted for 10 Nobel Prizes, and scientists from Bell contributed significantly to the Manhattan project. William Shockley left Bell to create Shockley Semiconductors on the West Coast, from where Intel was born. You could say that Silicon Valley itself was born out of Bell Labs.

But it all started with the ‘absurd’ goal of delivering long distance calling across the USA within 5 years.

Einstein said “if at first an idea is not absurd, there is no hope for it”. He was talking of course about scientific ideas which would have no hope of changing how we think about the world. A big goal can’t just be a continuation of what you’re currently doing. It’s got to push you beyond the ordinary, and force you to do something very different, way beyond your comfort zone. It’s got to sound next to impossible. If you were a cartoon animation, this is the idea that makes your eyes pop out of your sockets. In short, the idea has to be absurd.

A simple test of this is to ask what do you need to do differently from today (not just more / better/ bigger/ faster) to get to this idea. And if the answer is not different enough, maybe you need to sharpen your idea, or aim higher.

There is truth in the saying ‘aim for the moon so you can hit the trees’, but we’re not talking for big goals as a means of motivating yourself to hit the little ones. No, we’re talking about big goals you actually want to get to, and are willing to move mountains for. Always remember the wise words, “…the real risk is not that we aim to high and miss, but we aim too low and reach …”

Prepare for a Difficult Journey

It seems fairly obvious to say that getting to your big goal will usually involve an arduous and risky journey.

“An army officer’s family gets massacred. He remembers two junior officers who had been court-martialed. They are rascals but also brave. The officer decides to enlist them in his mission for revenge.” This was the 4-line story summary for the movie Sholay that the writers Salim / Javed peddled to Ramesh Sippy sometime in the early 1970s. Sippy had made a couple of hit movies, was still in his late 20s, who wanted to make a big movie, inspired by movies like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and the Seven Samurai. Over the next 3 years, Ramesh Sippy and his crew pulled out every stop to make a path breaking film. He decided to shoot the film in 70mm film which had never been done before in India. They also decided to use stereophonic sound which also couldn’t be done in India. (It turned out that the sound was done in a studio in Twickenham). Just to remind you about how audacious this was, movie theatres would need to upgrade their audiovisual infrastructure to screen the film. It was a long film - 3 hours, in fact. Which meant that theatres would also have to change their timings to accommodate it. When the movie finally got to the censors, they wanted last minute changes to the ending. When the movie hit hit the trade press, they were lukewarm, even to the point of disdain. One reviewer said it would be “… a sad experience for the distributors”. Launched on 15th August, 1975, it took a few months before it became apparent that the viewing population actually liked the movie. As everybody knows now, Sholay has been the colossus of Bollywood films for the past 50 years. It was an unprecedented and since unmatched commercial and cultural success. In the Minerva theatre in Mumbai where it was first released, it ran to full houses for 5 years. In 1999, BBC India called it the film of the millennium.

Be Resilient

Indian cricket is rife now with rags to riches stories, and parents sacrificing much else, and putting their time and effort into their childrens’ sporting futures. But even in that context, Yashasvi Jaiswal’s story stands out. He left his home in UP at age 10 to go to Mumbai to play cricket, in 2011. He worked in a shop but was fired because he couldn’t make time given his practice schedule. He had to live in the groundsman’s tent as he had no other place to sleep, and sold street food to make ends meet. 3 years later, he was spotted by an academy who took him in. In 2023, Jaiswal made his debut for India. There is no right age for dreaming big, but you have to have deep wells of resilience.

In the case of Sholay, shooting ran way over budget and time, and took two years to complete. And everybody warned Sippy it wasn’t going to work out. But Sippy never wavered from his big vision. He stuck with his choice of heroes and villain despite all the advice to the contrary. The villain’s voice was a question mark and he was advised to use somebody else’s voice but he stuck to his guns there as well.

When Sylvester Stalone took the Rocky script to producers, he had a $300,000 offer from United Artists to sell the script for other well-known actors to play the lead role. But despite reportedly having only $106 in the bank, and no other income, he stuck to his guns and insisted that he had to play the lead role. Prior to that ABC bought the script and wanted somebody else to rewrite it and make it into a television-movie. Stallone ended up returning the money and taking the script back.

Build the Right Support

N. Chandrasekharan, the Chairman of the Tata Group or ‘Chandra’ as he’s affectionately known had this gem to share when I last heard him speak. He said when he gets a proposal for investment from one of the group companies, he normally grills them about why they need the funds and what they’re going to use it for. But when they’re able to show that they have a track record of success, he often asks them ‘why x, why not 10x?’

Felix Baumgartner is a famous base jumper and sky-diver. Having jumped off the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lampur, and the statue of Christ the Redeemer in Rio, he decided to attempt the worlds highest free jump - from about 130,000 feet - from the stratosphere. In doing so he would dive 39 kilometers, and break the sound barrier without the help of any vehicular power. It took him 5 years to plan and execute the jump in 2012 And I got to listen to him speak in 2019. I remember clearly when he was asked whether he described himself as a daredevil, he said he saw himself more as a risk manager. Every little detail of this kind of endeavour, he said, had to be meticulously planned. Which is why it took 5 years instead of 2 as he initially thought. For example, one of the first things he did was to appoint Joseph Kittinger as an advisor and mentor. Kittinger, then 84, was the holder of the previous record of 102,000 feet, set in 1960. According to Baumgartner, ‘he was the only person who actually knew what I’d be going through and could talk me through it’.

Leading up to the second world war, Germany had pulled ahead in technology, with access to better submarines, aircraft, and was on the verge of nuclear energy. Meanwhile the US had consistently rejected proposals for development of technologies such as radar, and were focusing instead on producing more conventional capabilities. In 1938, Vannevar Bush left MIT to start and run the OSRD (Office of Scientific Research and Development), with direct approval and support from President Roosevelt. The OSRD was designed to bring in the best of academia, invention, and engineering, much to the consternation of the existing establishment. In hindsight, it was the body whose work largely swung the war in the favour of the allies. Radar and the Manhattan project were both the outcome of the OSRD’s work). But to do all of that Bush had to ensure that he had the support of the President.

The bottom line is that if you’re embarking on an audacious project or goal, you’re going to be wrestling against all kinds of obstacles including technology, externalities, skill shortages, collaboration challenges, and many more. You don’t want to add your own organisation to the list of things if you can avoid it. In fact getting the support of your organisation might be critical to overcoming some of those obstacles.

Take the Losses / Learnings Even if the Optics are Bad

Elon Musk is a man known for his big ideas. And he is also literally building rockets for the moon and beyond, including living on Mars, and enabling space tourism through his company SpaceX. A few months ago, a SpaceX rocked exploded after take off. It generated a lot of derision at the time especially because of Musk’s describing it as an “rapid unplanned disassembly”.

But look a little deeper, and a few things become more visible. SpaceX’s vision is not only to get the rocket to the moon, but dramatically bring down the cost of space travel by ensuring reusability of rockets. And while NASA’s modus operandi is to plan meticulously and get everything right, Musk’s approach is to learn faster. Since 2010, SpaceX has launched about 6 times as many rockets as NASA. In fact the reusability is one of the factors behind the rapid turnaround time between launches.

SpaceX is actually on a much faster timeline to get to their goal because they’re willing to take the losses and learnings. Despite the tendency to hide our failures, or to keep the world from laughing at us, the lesson is to flip that logic on its head and actually own the failure. In the most recent launch, the rocket took off and reentered, and the critical component, the seal holding the flaps did their job.

This is the nuanced point about failure. Recent innovation literature has to some extent turned failure into a badge of honour. But it’s important to fail correctly - in other words, fail quickly, often, and keep improving. Sometimes you also have to publicly acknowledge the failure, so that people can get past that point. Else it can get swept under the carpet and not actually get resolved. This is true of marginal as well as disruptive innovation, and in a sense, a big bold idea in execution terms is often a series of small innovations executed very tightly and close to each other, building exponentially and culminating in something extraordinary.

Book Review: What’s Our Problem, by Tim Urban

This is one of those books that everybody should read and absorb. For me the book has 2 key parts.

The first is a thinking model, which builds an excellent framework for how we look at society and its factions. We are conditioned to think about the right and the left of the political divide. But Urban wants us to think about high thinkers and low thinkers. High thinkers are like scientists who are open to questioning everything - even things they consider to be absolutely true. They are open to debate and will re-assess their position given new data. The low thinkers will dismiss everything that disagrees with their point of view. A group of high thinkers will be like an idea-lab - full of debates, new data, discussions and explorations. A group of low thinkers is what Urban calls a golem. An echo chamber of very little new thought. Consequently, high thinkers on the left and right will end up being centrists, as they will evaluate every idea, principle, or policy on its own merits and take their independent stand on each of them. On the other hand low thinkers will simply adopt the tenets and directives of whatever the group believes without question. Rather than the left and right, it’s far more important that we recognise the high and low thinkers. And Urban’s contention is that the world is being taken over by low-thinkers.

The second part of the book is a takedown of Social Justice Fundamentalism. We often tend to think of the low thinkers as typically right wing and having orthodox views on most subjects. However, Social Justice Fundamentalism is the low end thinking version of the left. It takes issues such as diversity and inclusion, and gender and race discussions to an extreme point of adherence at all costs, and zero debate. To me this was an eye opener - the shift from pluralism to purity of thought. From discussing justice and inclusivity to rabidly attacking any viewpoint that dares to question these tenets is a big shift. It’s a reminder that low thinking can happen on either side of the spectrum.

I was expecting the book to also cover other forms of low thinking but I suppose some of those are fairly obvious and the point is well proven through this one example. Go read the book.

AI Reading

Why the Rabit R1 device might not be all it’s cracked up to be. A hint: it’s mostly RPA. (Medium)

Path to AGI: Leopold Aschenbrenner this week posted this tome - talking through his thoughts on the imminent arrival of AGI and superintelligence. Essential reading for anybody interested in AI. (Situational Awareness)

Other Reading

Scott Galloway - there’s too much hoarding and ‘giving’ is just a misnomer. (Prof Galloway)

Neural: The transformative potential of computerised brain implants. (FT)

How to drive change: teenage players in the US Women’s Soccer System (Washington Post)

Thanks for reading, see you next week.