205: Cows, Cars, and Healthcare

Innovation in Healthcare - why it's harder than it looks. And Art. And writing. And Apple.

Racehorses, Cars, and Cows:

Thoughts From The Digital Health Innovation Summer School, Maynooth 2023

This should make anybody think:

I heard an interesting story recently at the Digital Health Summer School at Maynooth, Ireland about the way in which race horses are monitored nowadays, and the amount of data about their health and performance that can be seen on a mobile phone.

Also, farm animals are often tracked with sensors, so predictive healthcare can be provided for illness, births, and other scenarios.

Of course all of us have cars with enormous amounts of data which allow us to track and evaluate not just the overall car but a vast number of components.

All of this points to the curious phenomenon that we track the health of our Cars and Cows more diligently and proactively than we do our own health. A point made eloquently by John Shaw of Carelon. And something I've mentioned earlier.

Which is weird because cars can be replaced. Your body, largely, cannot.

It also means our current way of monitoring healthcare, is essentially based on responding when something goes wrong.

In a nutshell, in the words of Jerome Adams, we are doing the equivalent of driving in the night without headlights and relying on bumping into things to navigate.

Why is this? Nobody logically thinks this is a good way to be. What could be the blockers?

A part of the difference is that cars and cows have this done to them. They are passive, choiceless entities. Humans aren't. Humans have very strong views about choice. And I don't think the choices and implications are actually well presented.

A second challenge is the potential data risks are greater. The reality is that we have yet to truly trust that our data will be looked after, adequately. Note - I don't think this is about every potential extreme scenario. It's about basic adequacy of the data stewardship. It's still patchy.

A third and potentially critical one is the support from all the professionals involved. I met Karen Kelly, an advanced nursing practitioner, who told me that with a hand held ultrasound device she can now look at a patient and tell if there's something wrong, like a breached baby, or sometimes something she can't really identify, but knows is wrong. This device could revolutionise healthcare. But the problem is that any new technology devalues the years of training and knowledge accumulated by 'experts' - so adoption is stymied by rejection by the senior medical people.

A paper by Janet Hughes, George Crooks and others estimates that it can take up to 17 (seventeen!) years for digital health adoption, based on service readiness levels.

How to fix this?

A design pattern of technology is that it democratises expertise. The way a smartphone can do what you had to learn to do with a DSLR camera. Or an automatic transmission does what it took you time to learn with a gear shift. And photographers who learnt to craft their pictures with a DSLR (like my wife) feel they've lost something with the automation and intelligence, or people who have learnt to drive with a gear shift, (like me) sometimes feel something's missing with an automatic. Sometimes, technology doesn't take away the human input. New smartphones allow you to play with the same controls manually. But you have to re-learn the 'how'. We sometimes assume experts will get it but they need retraining too.

A second design pattern of technology is that it democratises luxury. A simple example is personalisation - which was once the preserve of the rich, and in many categories (build your own cycle, or customise your shopping experience) is now increasingly available to everybody. Athletes are often monitored for a vast number of things while they train and perform. This is currently a luxury as the performance of professional athlete's are (like racehorses) a matter of commercial value. But technology can increasingly make the same capabilities available to us. Footballers when they are exhausted are said to be in the 'red zone'. Why not us? Usually this is a commercial problem.

Two more issues need addressing. The way emerging tech is presented and introduced, and the choices to be made, to all stakeholders needs what is now encapsulated in design thinking and systems thinking. Plenty of experts do this well, they need to be at the coal face of this. And of course it goes without saying that there needs to be demonstrably better stewardship, whether that comes via the health authorities, or via decentralised and tokenised systems.

None of this is straightforward. I can be glib in writing this but of course, talking is the easy part. It's the doing that counts. Here's hoping.

The Constancy of Change

Last week at The National Gallery we welcomed our clients for an evening of great conversations and camaraderie at the Tata Consultancy Services Summer Reception. And as I looked around, I suddenly felt that the setting could not have been more apt. Painting and portraiture were dramatically disrupted by photography (in part leading to the birth of impressionism), and while portraits could enhance your looks, photography was less kind. And yet almost two centuries later we've come full circle today with filters and AI. The themes of disruption and regeneration were all around us.

But more than anything else, this picture caught my eye. It's an allegorical painting by Pompeo Batoni from 1746. It's titled 'Time Orders Old Age To Destroy Beauty' - and is a very fitting reminder of the only constant being change. Today's shiny toy will become tomorrow's jaded plaything. Which is why we must keep creating, constantly, to stave off irrelevance and destruction.

Creativity and Luddites

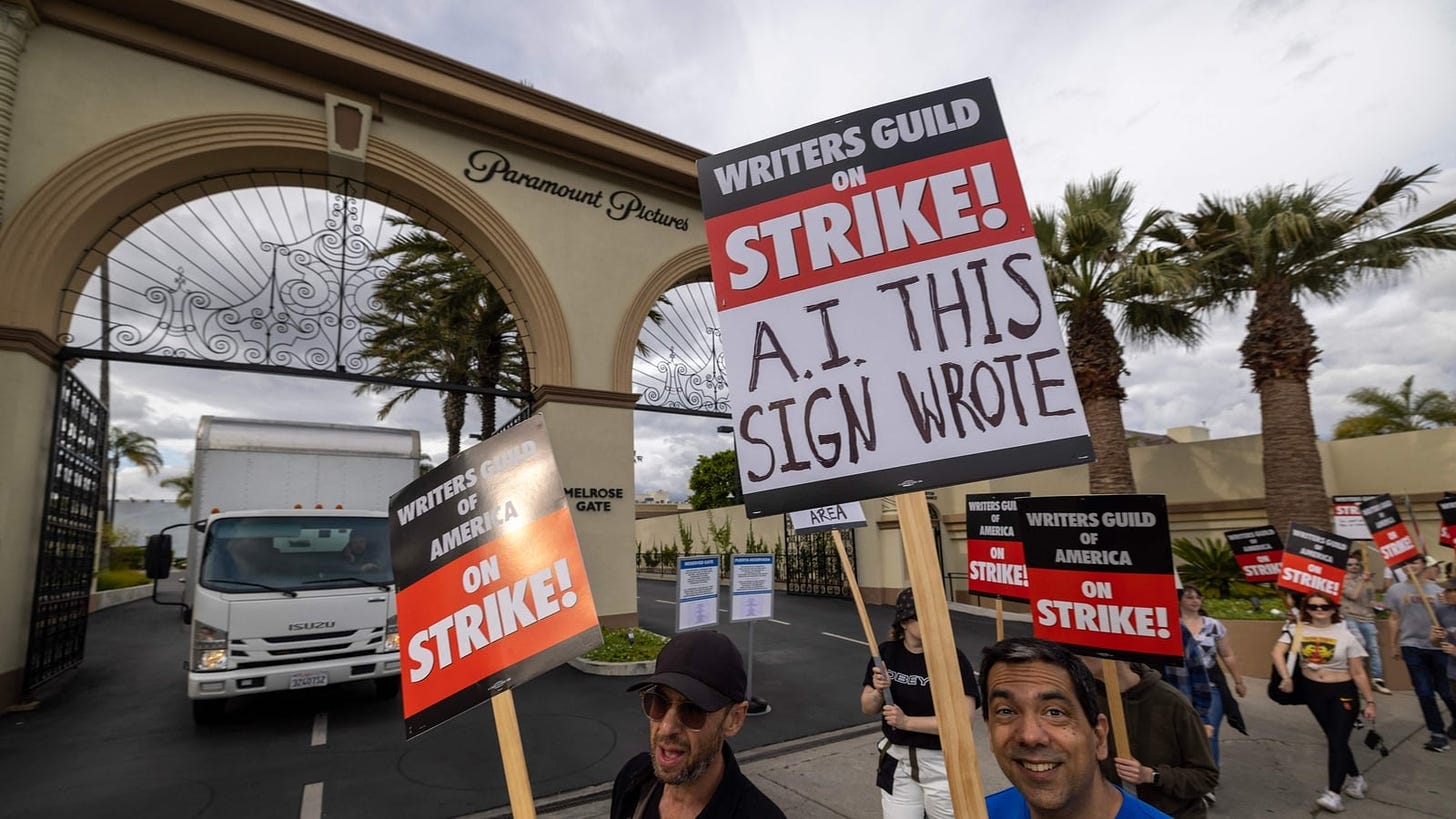

On the BBC Tech Lives podcast, I heard Justine Bateman, writer, actor, director and producer talk about AI and its impact on Hollywood. Interestingly despite her experience in multiple roles, her position was particularly extreme and I found a myself disagreeing quite a bit.

She argued in sum that (1) AI was worse than other technologies because this was existential to creative jobs (2) that ultimately this was removing the critical 'human' emotion and human creative endeavour from films and (3) it was not going to make films better, but rather just contribute to the profits of studios. (4) she also suggested that AI has zero originality, and that it's just ripping off from existing actors and writers.

My observations:

(1) Generative AI is an existential threat to writers in exactly the same way that digital distribution was, to projector operators in movie theatres. It's not new, it just suggests that this set of people perhaps a more strident voice.

(2) It's an interesting argument whether writers and actors' needs to express themselves is the cornerstone or whether it's the audience's desire to be entertained. If it's the latter, then it doesn't matter whether the script was written by AI or a human or both, as long as it was enjoyable. If it's the former, AI won't prevent people from writing or acting. They just won't as get rich doing it. Much like the world before big budget films.

(3) This can only be decided over time - we've already had examples of AI generated images winning photography contests. I suppose only the audience decides this if we're talking commercial success.

(4) Debatable point on both counts - the experience of chess with Deep Mind shows that AI ends up making moves to win games that humans would not think of making, so it is actually being creative. And I'm yet to meet a human whose creativity is not built on absorbing and repurposing the thoughts of others to some extent.

The Luddites were not people who didn't understand technology, but rather people who were against it. They were smart enough to see exactly what it would do to their livelihood. Hollywood writers are today's Luddites. They are right in fearing the impact of AI on their livelihoods, but like others, they are probably wrong in their morally righteous defence. Their cause is no more and no less holy than the boatmen who lost their livelihood when bridges were built.

Other Reading

Using AI: While I disagree with the over-simplified replace vs augment premise, this is a useful outline of skills and capabilities in order to work with. Humans will require ethical thinking, cooperation, and emotional awareness to compete with AI, and skills in data and algorithmic models to collaborate. There’s a similar list of skills AI will need to compete and collaborate with humans. (HBR)

India stack: India has built a model comprising identity, payments, and data management which operates at population scale, run by the government, which is popularly called the India Stack - partly because India is exporting this to other countries. Tools like MOSIP, the product version of Aadhar, are being trialled by The Philippines, Sierra Leone, and Sri Lanka. The longer aim might be to become a dominant global payments leader. (Economist)

The Chip Story: Under the hood of AI, there is still ongoing progress and plotlines at the memory and chip level. Needless to say there’s a huge demand for DRAM and memory and this includes companies other than nVidia. For example Korea’s SK Hynix Inc. and Boise-based Micron Technology Inc. command 52% of the global market for dynamic random-access memory (DRAM). Combined, they’re worth just $140 billion. Their only rival, Samsung Electronics Inc., accounts for 43% of the DRAM industry — just one of at least four global sectors it leads — while it trades at $317 billion. So while nVidia hogs the glory, perhaps there are other players to watch. (Bloomberg)

Economics of Ageing Populations / "in much of the world the patter of tiny feet is being drowned out by the clatter of walking sticks." such as Thailand, Brazil, and Mexico. The largest 15 countries by GDP all have a fertility rate below the replacement rate. That includes America and much of the rich world, but also China and India, neither of which is rich but which together account for more than a third of the global population. But whereas the rich world currently has around three people between 20 and 64 years old for everyone over 65, by 2050 it will have less than two. The implications are higher taxes, later retirements, lower real returns for savers and, possibly, government budget crises. (Economist)

ChatGPT and Meaning: Geoffrey Moore, the author of ‘Crossing the Chasm’ makes an interesting set of observations about ChatGPT but arguably the few lines of conversation after his piece are as valuable if not more! (LinkedIn)

And One More Thing…

How can we not mention the arrival of Apple's Mixed Reality headset? Part laptop, part meeting room, part gaming platform, part television, Tim Cook calls it the first apple product you look through rather than look at. This is an Apple super power - the ability to change human behaviours with new products. From the first smart phone, to iPads, to the introduction of Apple Pay, to apple watches, each has relied on a mass adoption of a new behaviour, and often, succeeded. And arguably, it's that ability to describe the experience in human terms - "look through rather than look at" - which is key to this ability. The Vision Pro seems to score high on many usability areas compared to the competition - including comfort, ease of use, weight, etc. and yet, there are tensions within Apple when it comes to design versus engineering. Some have called this the point where Apple stops being a design led company. But three things stand out for me. The first is Apple's ability to change the conversation - in this case from Metaverse to 'spatial computing' - which instantly makes more intuitive sense. The second is the arrival of a VisionOS - a reminder of Apple's ability to build from ground up and also to brand and highlight the operating systems of its products. And the third is my guess that the price point of approximately $3500 is designed to create a small test market of technology enthusiasts and rich people - for both of whom the joy of having an early stage and cool toy will outweigh any product and performance challenges. It might also be a sign that Apple isn't quite ready for the mass market just yet.

See you soon

Ved